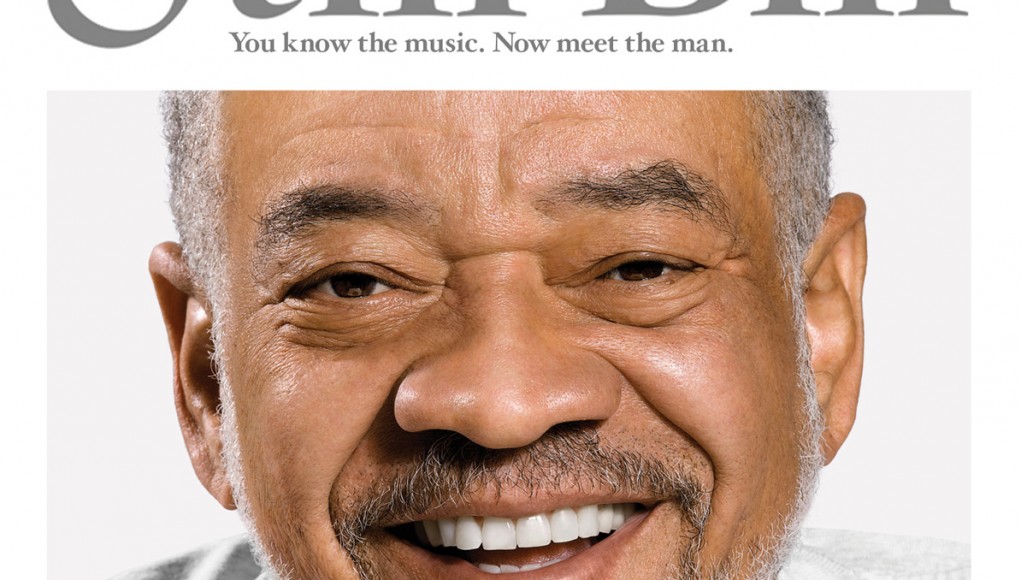

Bill Withers was rather different from most other musicians. He did not have a depressing story to tell, he never thought of himself as cool, he chose to start his music career at thirty-two, and he never had interest in being mainstream. Unlike many musicians who overstayed their welcome, became burnt out, or passed away far too young, he chose to leave the music industry at the height of his career. Like Withers himself, Still Bill is not your typical rock documentary, particularly because his career does not have the roller coaster ride that many before him have experienced. Instead the documentary focuses on his ideals as being a common man and transcribing that mentality first to his music and then, later in life, as a father.

Withers left his music career at the top, but as of 2010, he is well and healthy and still retains his wisdom and poetry. Along with his wife and grown children, he resides in a comfortable lifestyle and enjoys his life at a leisurely pace. He fiddles with the knobs and buttons on his home studio, but does not know exactly what to do with everything. Close friends insist that while he may not publish music anymore, there is no doubt he is writing and playing.

Withers grew up in the segregated South. He shows very frankly where the well-kept white cemetery is, and where the black cemetery is, hidden in the forest. He had to purchase ice cream from the back door of a store.

One of the most amazing aspects of Withers’ life is that as a child he had a stutter. He avoided the phone, talking in public, and anywhere he was told to “spit it out.” For a musician who had written some of the most poetic lyrics that did not exactly fit into radio friendly formats, Withers had realized that his stuttering made others nervous, and thus he chose to put them at ease.

The day after he had been laid off from making toilets for airplanes, he was invited to Johnny Carson. In a discussion with Dr. Cornel West and Tavis Smiley, he explains that people who thought of themselves as experts in black culture (read: white executives) asked where his horn section was and if he could cover “In the Ghetto” by Elvis, a suggestion that infuriated him. In the same discussion Withers explains that many deemed him a sellout, but his wisdom was ultimately proven: the only thing that sold out were the seats, the sign of a successful entrepreneur.

While the film does examine Withers’ past, if anything, it reveals his present. He is still a loving husband and father, a dear friend, and man who has made the best of his opportunities. Still Bill is indeed a reflection of Withers’ ideologies; he is still the man he was when he was a stutterer, in the Navy, assembling toilets, starting a family, and leaving his career. He never wanted anything more than to be Bill, and this documentary reflects that in an exceptionally accurate form.

I have included a YouTube video of Withers’ “Hope She’ll Be Happier” from Live at Carnegie Hall, one of my personal favorites of Withers’ songs and albums.